Bay of Pigs Vets Fight for Home

Betrayed by the U.S. government and their own country, they want to be remembered.

By Janine Zeitlin Thursday, Jan 17 2008

Around dawn on April 19, the sound of rocket fire abruptly roused Eduardo Zayas-Bazán from restless dreams. He lay in a trench with a submachine gun and a .45 on Girón Beach on Cuba's southern coast. A gray B-26 strafed Blanco's bar, a rustic, open-air bohÃo just 150 yards away.

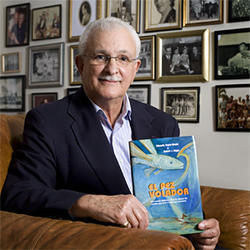

Eduardo Zayas-Bazán spent more than two decades working on a fictional book based on his time as a frogman.

Blas Casares, a frogman, questioned President John F. Kennedy about why he pulled American support for the 1,400 exile fighters.

January 12, 2011

It was a pleasant spring day, around 80 degrees. Blanco's had been a hideout and headquarters for Eduardo and his friends. The previous night they had shared a hearty ajiaco â vegetable and pork stew â before retiring to their foxholes.

After the plane passed, the muscular, dark-haired 25-year-old spotted four fellow fighters entering the bar. "I need to warn them," he told his compadres before rolling from the trench and sprinting toward the men. His face and hands were painted black for camouflage. He wore dark green khakis. The men mistook him for a Cuban militiaman. They began firing.

A bullet seared through his right leg and pummeled him like a heavy hammer blow. He crumpled to the ground and yelped, "¡Ãguila negra! ¡Ãguila negra!" ("Black Eagle"). His friends joined in screaming the code word.

The men stopped shooting, but the damage had been done. Eduardo joined the victims Ââ whose wounds portended the day's outcome. Not far away, in a makeshift hospital, intestines spilled from the body of a man who begged for morphine. An officer's chest was hollowed out by a bullet. White sheets covered a row of rigid bodies.

Eduardo's friends ran from the foxholes and surrounded him. There was José Enrique Alonso, their fortyish leader, whom the young men called abuelo. Next to him was Jesús Llama, whom they called "Chiqui" (even though the six-foot-tall soldier in his twenties had long outgrown the boyhood nickname), and cousins Jorge and Felipe Silva; both young men had quit school to join the force.

They yelled for a medic, and minutes later, one arrived to clean and bandage Eduardo's leg. A doctor told them about a plane leaving soon for Nicaragua to evacuate the wounded. A dusty, beat-up pickup truck pulled up to the bar.

"You're a lucky man," the doctor told Eduardo. "You'll be able to get out of here."

His comrades carefully shifted the weakening Eduardo onto the truck bed and bade him farewell. Five minutes later, when the truck pulled into the isolated Girón airstrip, the plane had already left. Remembering the gold Virgin Mary medallion around his neck, he prayed for his life, his young wife Elena, and their son, his firstborn and namesake, just five months old.

Eduardo and four others in the advance force that day in 1961 â the Bay of Pigs frogmen, hombres rana â were later captured by Fidel Castro's army and paraded through the country. They and the 1,400 other exile fighters would be used as propaganda for almost a half-century to illustrate the gringos' atavism toward the Cuban revolution. Castro later built a museum on Girón Beach â on the Bay of Pigs â dedicated to their failure. Thousands of Cubans are bused there annually to celebrate.

Likewise, the men of Brigade 2506 and that band of frogmen want their story memorialized. They hope to be known worldwide as more than a botched attempt by homesick immigrants and American mercenaries.

And in Miami, cradle of the Cuban exile, they're being taken seriously. This past September, county commissioners agreed to study a plan to give Bay of Pigs veterans a prime, nearly three-acre slice of bayfront real estate behind the American Airlines Arena for a five-story museum dedicated to the Cuban exile experience. Supporters are confident they can raise the estimated $65 million needed to construct the 80,000-square-foot building.

Answers are expected soon.

They want everyone who comes here to know that Miami and Cuba would not be the same had the brigade and the frogmen succeeded.

"It was almost like a crusade," says Eduardo Zayas-Bazán, his impassioned voice rising. "We knew we were defending a just cause. Through the years, it's become almost like we were the bad guys. But we were fighting for democracy."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eduardo was an All-American swimmer in high school. He began competing at age seven and toughened his body with 50-yard sprints. But that didn't prepare him for several minutes in an ice-filled pool behind a luxurious South Miami home in December 1960. Eduardo was among the stout 20 or so men who endured the chill until the Americans ordered them out. Less than six months before the invasion, Eduardo stood among the others, teeth chattering and clothes dripping.

Their trainers, "friends of the Cuban cause," had dumped the contents of an entire ice truck in the water. Mist rose from the surface as the frigid water clashed with steamy Florida breezes. "We thought it was weird because we were going to be swimming in the tropics," Eduardo says. "There was no need for that, but I suppose that was part of the psychological training period. "

Eduardo was born into a political dynasty. His great-grandfather was a member of the first Cuban senate after the island gained independence from Spain in 1902. His great-great-uncle was the first governor of Camagüey, a fertile, cattle-rich central inland province that includes a yawning Texas landscape. And his grandfather, Rogerio Zayas-Bazán, was a high-ranking official overseeing the police for the young republic. When Rogerio was killed in a gun duel in 1931, Eduardo's father, Manuel Eduardo, returned from studying at the University of Georgia and became a congressman three years later at age 22.

Cuba, España y los Estados Unidos | Organización Auténtica | Política Exterior de la O/A | Temas Auténticos | Líderes Auténticos | Figuras del Autenticismo | Símbolos de la Patria | Nuestros Próceres | Martirologio |

Presidio Político de Cuba Comunista | Costumbres Comunistas | Temática Cubana | Brigada 2506 | La Iglesia | Cuba y el Terrorismo | Cuba - Inteligencia y Espionaje | Cuba y Venezuela | Clandestinidad | United States Politics | Honduras vs. Marxismo | Bibliografía | Puentes Electrónicos |

Organización Auténtica